Alcohol consumption and its impact on blood sugar

The alcohol we consume in the form of wine, beer, and spirits is called ethanol. Ethanol is produced through the process of fermentation of sugars by bacteria or yeast. Depending on the drink, you will find more or less ethanol to be present. Although there has been much discussion over the years as to whether or not alcohol in moderation may actually be beneficial for consumers, the tone in recent publications has changed significantly stating that the risks will always outweigh any potential benefits. One of those risks is cancer.

What kind of alcoholic beverage you consume is thereby irrelevant. The risk remains as long as ethanol is present. Why? Because in the process of breaking down ethanol within our bodies, which happens for the most part in our liver with the help of enzymes, a toxic compound is produced which, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, is also a known carcinogen (a substance capable of causing cancer). Whether you have food with your alcoholic drink or a lot of water will not eliminate the risk.

Consuming alcohol of whatever kind is therefore a choice of pleasure and not of health.

Nevertheless, the notion that small to moderate amounts of alcohol are better than large ones still holds true. The UK’s low risk drinking guidelines state in order “to keep health risks from alcohol to a low level it is safest not to drink more than 14 units a week on a regular basis.” The number of units thereby depends on the size and strength of the drink. As an example: one 125 ml glass of wine (14% ABV) equals 1.8 units. If you are interested in checking how many units you consume on a weekly basis, check the Unit Calculator by alcoholchange.org.

The effect alcohol in small to moderate amounts usually has on the body range from feelings of relaxation to a sense of euphoria. It can become dangerous, however, if excessive amounts are consumed. Short-term effects can include impaired motor skills, slurred speech, and changes in perception. The long-term effects of excessive drinking can be even worse ranging from heart-related issues to liver diseases. In her book Glucose Revolution, Jessie Inchauspé also sees alcohol as a contributor to inflammation and with that to inflammation-related illnesses.

In the following, we shall take a look at the impact of alcohol specifically on type 1 diabetes as well as type 2 diabetes. At the end of each of those sections, you will find some tips on how to consume alcohol more safely if you or a loved one lives with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) and alcohol

Type 1 Diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the beta cells of the pancreas have been destroyed which makes it impossible for the pancreas to produce the hormone insulin. The main function of this hormone is to lower the glucose levels within our bloodstream by making sure that the cells in our body ‘absorb’ the glucose which can then be used as energy within them. In collaboration with our liver (and skeletal muscle), insulin will also make sure that any excess glucose is stored in the liver cells (as glycogen) to be released again during times glucose levels within the body are running low.

Our liver thus plays a very important role in the regulation of blood glucose regulation.

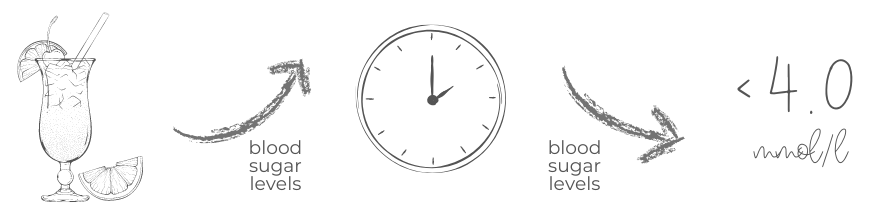

In Scheiner’s Think like a pancreas, he talks about the effect of alcohol on the liver and blood sugar levels and how alcohol is a roller-coaster factor given its property to cause blood sugar levels to both rise and fall. The rise in blood sugar levels (hyperglycemia) would usually happen in the short term and be the result of carbohydrate-rich beverages such as beer or drinks mixed with fruit juices for example. However, in the long term, due to alcohol’s property to suppress the liver’s secretion of glucose, low levels of blood sugar (hypoglycemia) will have to be expected.

Scheiner goes on to explain that given Hypoglycemia’s symptoms and their similarity to the signs of being ‘drunk’, this state can become very dangerous as both the person affected as well as people around them will likely struggle to recognise the true issue. Note that the risk of hypoglycemia remains present for up to 24 hours after you have stopped drinking alcohol.

Now the other extreme is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) which can occur when blood sugar levels are high (hyperglycemia) and remain high for a prolonged period of time due to a lack of insulin. As mentioned earlier, insulin is required for the cells in your body to ‘absorb’ and use the glucose in your blood. So if there is no insulin your blood sugar levels are running high but your cells don’t get the energy they need in order to function. The body’s reaction is to burn fat to make up for that lack of energy. In the process of breaking down fat, however, ketones are released which can make your blood acidic.

DKA can have many reasons. Alcohol can contribute to DKA in that it works as a diuretic (makes you wee more often) and because it can simply make you forget to take your insulin.

To consume alcohol more safely, here are a few tips if you or a loved one is living with T1D:

- Stick to the UK’s low risk drinking guidelines (14 units a week).

- Make sure to not drink alcohol on an empty tummy as this may exacerbate hypoglycemia.

- Drink non-alcoholic fluids with your alcoholic beverages to make up for water loss due to the diuretic effect of alcohol.

- Stick to beverages like wine and spirits that don’t result in the roller-coaster effect (from high to low) and make managing blood sugar levels a little easier

- Try and stay within a state of mind that still allows you to take regular blood sugar readings.

- Stay on top of your ketone levels.

- In his book, Scheiner also recommends being a bit more careful when administering basal insulin to accommodate for the drop in blood sugar levels. But please do consult your Diabetes Specialist before making any adjustments to your insulin dosages.

- To counteract the initial rise in blood sugar when drinking a beer, for example, you will likely find yourself administering bolus insulin. The NHS recommends only administering the amount of insulin necessary to cover half the estimated carbohydrate content of the alcoholic beverage. Again, this is to avoid exacerbating potential hypos later on.

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and alcohol

Type 2 diabetes differs from type 1 in that it is not an autoimmune disease and is often linked to the lifestyle and even genetics of an individual. Insulin in individuals living with type 2 diabetes is either not produced enough by the pancreas or the insulin that is produced is not working properly, a phenomenon which is called insulin resistance. In some cases, insulin injections will become necessary for type 2 diabetics. According to diabetes.org.uk about 1 in 4 individuals with type 2 diabetes take insulin.

Given the nature of T2D, alcohol can take on different meanings. Citing multiple studies, the Harvard School for Public Health, emphasis in this article how small to moderate amounts of alcohol can lower the chances of an individual developing T2D. Excess alcohol consumption, on the other hand, will likely increase the risk of developing T2D. Due to the caloric value of many drinks, the risk of putting on weight which in turn can contribute to T2D is also present.

As with T1D, individuals living with T2D should be careful when consuming alcohol to keep their blood sugar levels in check and avoid hypos – whether that is through the amount of alcohol or even the kind of drink consumed. This is especially important if insulin or certain medications are taken. The type of drink can be of particular importance if obesity is part of the issue. One pint of beer can have around 200 calories alone. A glass of red wine (250ml) can go up to around 225 calories. On a night out, calories can add up quickly this way especially once the alcohol-induced peckishness sets in.

Just like anybody else, type 2 diabetics should be mindful when consuming alcohol.

Here are some tips that may help:

- Do not exceed the 14 units of alcohol a week stated within the UK’s low risk drinking guidelines.

- Avoid having alcohol on an empty stomach as this may exacerbate hypoglycemia and may cause other issues.

- Make sure to have water or other non-alcoholic fluids with your alcoholic beverages to balance out any water loss due to alcohol’s diuretic effect.

- Stick to beverages that are lower in calories but don’t raise your blood sugar levels too much, e.g. clear spirits mixed with soda water

- Be mindful of your blood sugar and take regular readings

Conclusion and additional resources

Having a drink in a social setting or even after a stressful day at home shouldn’t be frowned upon. I enjoy the occasional drink and I am sure many of you do too. However, we do need to keep in mind that alcohol is a drug. Knowing that should make us more alert and sensible as to what is too much and when it is time to stop. Diabetic or not.

When you make any choices that will likely have an impact on your health, make sure to do your research. This is especially important if you or a loved one of yours is living with diabetes. SANGDOUX was born from the idea of providing more information and for individuals to make more informed choices. If you have anything to contribute, or would like to share your experiences or specialised knowledge, we would love to hear it. Please drop a message in the comments section or get in touch with us.

If you want to read up more on the topics discussed in this post, please refer to the bibliography which lists all the sources used for creating this post.

Bibliography

Department of Health (2016): UK’s Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines, link: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf

Department of Health and Social Care et al. (2021): Chapter 12 – Alcohol, link: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention/chapter-12-alcohol

Diabetes.co.uk (2019): The Liver and Blood Glucose Levels, link: https://www.diabetes.co.uk/body/liver-and-blood-glucose-levels.html

Diabetes.org.uk (2023): what is dka (diabetic ketoacidosis)?, link: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/diabetic_ketoacidosis

Diabetes.org.uk (2023): Alcohol and diabetes, https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/enjoy-food/what-to-drink-with-diabetes/alcohol-and-diabetes

Diabetes.org.uk (2023): Insulin and type 2 diabetes, link: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/treating-your-diabetes/insulin/type-2-diabetes

drinkaware (2021): Is alcohol good for the heart?, link: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/health-effects-of-alcohol/effects-on-the-body/is-alcohol-good-for-the-heart

Harvard (2022): Alcohol: Balancing Risks and Benefits. Moderate drinking can be healthy—but not for everyone. You must weigh the risks and benefits. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-drinks/drinks-to-consume-in-moderation/alcohol-full-story/

Inchauspé, J. (2022): Glucose Revolution, The life-changing power of balancing your blood sugar

Knowledge4Policy by European Commission (2021): Alcoholic Beverages, link: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/alcoholic-beverages_en

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2022): Alcohol’s effect on health. Research-based information on drinking and its impact, link: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/alcohol-metabolism#:~:text=The%20Chemical%20Breakdown%20of%20Alcohol,eliminate%20it%20from%20the%20body.

NHS (2022): Risks. Alcohol misuse, link: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alcohol-misuse/risks/

nidirect.gov.uk (n/a): What happens when you drink alcohol, link: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/what-happens-when-you-drink-alcohol#toc-0

Scheiner, G. (2004): Think like a pancreas, A practical guide to managing diabetes with insulin

World Health Organization (2023): No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health, link: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health